One Friday within the spring of 1971, 5-year-old train enthusiast Michael Meadows and his grandmother boarded the northbound train to Nashville at Chattanooga’s Union Station. Meadows’ grandfather was a train man, The Chattanooga Times reported, and Michael Meadows hoped to follow suit.

Probabilities looked dim. Young Michael was set to board the last ticketed passenger train to Nashville. The very next passenger train to depart Union Station, southbound to Atlanta, would mark the top of business passenger rail service in Chattanooga.

Michael’s mother, Mrs. William T. Meadows, said she had explained the situation to the boy. “But he just cannot understand why he won’t find a way to ride the train back to Chattanooga when he’s ready to come back home,” she told the Times.

In a city once defined by trains, a version of Michael’s bewilderment would echo for the subsequent half-century. Even intercity bus lines are actually scarce. When you’re a Chattanoogan who desires to get to Nashville, Birmingham, Alabama, Atlanta or someplace else, it’s generally expensive or inconvenient to achieve this and not using a automobile.

Now, prompted by recent potential federal infrastructure money and a way that conditions are ripe for trains to reclaim their lost glory, lawmakers and advocates in Chattanooga are again talking of passenger rail lines to Nashville, Atlanta and beyond.

But, despite the existence of lively freight lines between those and other destinations — which generally run the identical tracks on which passengers once rode — the challenges are steep. State and native lawmakers have talked this talk before — in every decade, in truth, since essentially the most recent ticketed intercity passenger train left Chattanooga, greater than 50 years ago. Is that this time any different?

TRAIN FEVER

Trains, for a lot of today, evoke the hearty spirit of a bygone era. Mark Brainard, who studies the archives on the Southern Railway Historical Association, remembers a grim passing of the guard within the Eighties on the novelty steam train line where he worked in various capacities across the South, because the old engineers didn’t pass their wisdom and elegance to the subsequent generation.

“You bought these guys, 30 years old, used to running a diesel locomotive, that would not play the whistle,” Brainard said from his office near the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum. “They couldn’t work the whistle to present it a soul, right?”

Trains, for people living before us, nonetheless, embodied the astonishing possibilities of modernity.

“Nineteenth-century Americans experienced this radical reordering of their sense of space and time,” said William Thomas, a University of Nebraska historian of the Southern railroads.

Individuals who have lived through the web age might find a way to relate, he said.

Picture yourself. You are in 1820s Savannah, Georgia, where life takes place on the speed you’ll be able to walk.

However the newspapers carry strange tales: Across the ocean, a miraculous device uses steam to maneuver coal on roads of rail.

Skepticism was only natural. “There have been doctors who said, ‘Man cannot breathe air at such a high speed,'” Brainard said.

But train fever was spreading. People saw it as a transformational technology, Thomas said, “not only as an engine of progress, but as something that might transcend nature and help create a society of interconnected places.”

Staff photo by Erin O. Smith / .A Norfolk Southern freight train, lead by rebuild SD-60e no. 6976 makes it’s way down the mainline because the sun sets near Central Avenue Monday, Nov. 13, 2017, in Chattanooga, Tenn. At the fitting Norfolk Southern MP-15DC locomotive, no. 2399 sorts cars at an area industry near the Choo-Choo. Know as East End, quite a few trains a day traverse the world because the mainlines of each the Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads are only yards east of those yard tracks.

Staff photo by Erin O. Smith / .A Norfolk Southern freight train, lead by rebuild SD-60e no. 6976 makes it’s way down the mainline because the sun sets near Central Avenue Monday, Nov. 13, 2017, in Chattanooga, Tenn. At the fitting Norfolk Southern MP-15DC locomotive, no. 2399 sorts cars at an area industry near the Choo-Choo. Know as East End, quite a few trains a day traverse the world because the mainlines of each the Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads are only yards east of those yard tracks.Erin O. Smith

TRACKS LAID

To Georgia power brokers of the early nineteenth century, the Tennessee River promised access to the economies and raw goods of the West. Planners combed the maps. Between Lookout Mountain and Knoxville, there appeared to be a rare natural break within the Appalachian Range granting access to the river.

From Atlanta, builders headed northwest, dodged hills and small mountains, putting together a crooked railroad, stuffed with sharp turns, often inhospitable to multiple tracks, Brainard said.

While paid staff likely numbered amongst them, the people digging dirt and laying tracks were often not working of their very own free will. Thomas said he has consulted every annual report of a Southern railroad company before the Civil War. Those reports, produced for the advantage of shareholders, tallied profits, losses and assets — during which category corporations often reported the financial value of the people they enslaved.

Corporations in those days generally needed to be chartered by local governments; their rights and purposes were approved by lawmakers. Based on Brainard, Tennessee’s had made a decree: the railroad have to be within the state by 1849, lest the constructing company lose its rights.

By 1847 the tracks reached Dalton, Georgia, quite near Chattanooga — at the very least because the crow flies. But there was a mountain in the best way. Squeezed for time, staff left out it, leaving the tunnel for later, Brainard said.

They laid tracks from the opposite side of Chetoogeta Mountain, and arrived in Chattanooga in late 1849, with the road terminating around what’s now M.L. King Boulevard, Brainard said. Speculators, foreseeing a boom town, had bought all the things for a mile up from the river.

Soon the tunnel was accomplished, and the Western & Atlantic Railroad linked Chattanooga to an emerging railroad network that prolonged to the Atlantic. The brand new train terminus had its flaws. Down river toward Signal Mountain in those pre-dam days turned out to be at times almost un-navigable, given the whirlpools — “the suck,” it was called — a fact Indigenous groups were well aware of, Brainard said.

Still, Chattanooga’s identity was set. Soon, recent train lines stretched from Chattanooga into Knoxville and on toward mid-Atlantic cities. Recent tracks looped southwest with the river after which veered toward Nashville, supplanting the circuitous river routes or mud-slogged wagon trains through which, Brainard said, its wealthy residents previously got their fabrics, forged iron or Champagne from France.

Chattanooga Public Library / Three unidentified men in a locomotive belonging to the Roane Iron Company, which was incorporated in 1867 and positioned on the Tennessee River.

Chattanooga Public Library / Three unidentified men in a locomotive belonging to the Roane Iron Company, which was incorporated in 1867 and positioned on the Tennessee River.A WORLD CONNECTED

Chattanooga’s rail and river connections helped make it a strategic treasure within the Civil War, and after the fierce fighting ended, the railroad system continued to chaotically grow.

“They duplicated routes on a regular basis,” said Richard White, a Stanford historian who has extensively studied the financing of the railroads. “When you want chaos — and never everybody goes to agree with me on this — leave it as much as the private sector,” he said by phone.

Though the federal government famously poured in money and land grants for the transcontinental railroads, the Southern railroad was mostly a state- and privately-funded affair. Even local governments eventually pulled out, nonetheless. The highly competitive railroads often lacked the traffic to sustain themselves, and by the 1870s, railroads were going bankrupt, often leaving the general public holding the bag and engendering skepticism toward further government involvement, Thomas said.

The Jan. 19, 1880, Recent York Times captured the frantic energy of the train business, with an article describing “an enormous railroad scheme.” The Louisville and Nashville Railroad Co. had bought the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, putting to rest an epic rivalry during which, in keeping with the paper, the latter company had “set secretly and vigorously to work to checkmate” their competitor through a bewildering array of secret purchases, corporate coups, stock manipulations and backroom deals aided by the “influence of Southern friends” — until, eventually, in a Fifth Avenue hotel in Recent York City, the first stockholders of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad accepted there was nothing to do apart from sign away their shares and cede “Southern Railroad Supremacy.”

Chattanooga was the type of place over which such a supremacy was sought. By the Eighteen Eighties, Brainard said, snowbirds from Buffalo to Chicago funneled through Chattanooga, certain for the Florida winter. Trains conferred a unity upon the region. Chattanoogans in that point could take a train to many nearby railroad towns and onward toward every major city, to the south, to the west, to the coasts. The Chattanooga Times had a railroad editor, Brainard said, and its founder, Adolph Ochs, used privately chartered trains strategically to defeat his primary competitor, the Knoxville Sentinel, in a tug-of-war to supply news to railway towns in between.

But by the late nineteenth century, railroad executives had concluded that raft of passenger service was a consistent drain on an organization’s balance sheet, Thomas said. Freight moved en masse, with minimal labor and hassle relative to passenger service. Freight would not die in a crash. Freight couldn’t sue for negligence.

Still, the businesses kept passenger service due to their charter requirements, and the height of American ridership was yet to come back. By the turn of the Twentieth century, rail remained “the one option to move across vast interior spaces,” Thomas said. The beaux-arts Terminal Station opened in Chattanooga in 1909.

Trains for many years remained the medium for the nation and the events that shaped it. They carried mail and knowledge. They enabled the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to cities and economic opportunities within the North. The federal government took control of the trains during World War I, coordinating rates and schedules in an effort to efficiently move soldiers from far-flung regions — Nebraska, California — to the eastern seaboard for deployment.

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Travelers at a train station in 1959.

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Travelers at a train station in 1959.NEW MODES

David Steinberg’s mother told him his first word was “bus.” Born in 1939 in Alton Park on the corner of thirty eighth and Pirola streets, he watched as train cars from the Incline Railway went up Lookout Mountain — and from his porch as trains went forwards and backwards, day and night — the major line of the Southern Railway path to Birmingham.

Starting within the early Fifties, Steinberg took 1000’s of photos of the trains in Chattanooga during their slow and chronic Twentieth century decline and wrote multiple books on trains and buses because the world modified around him.

An Orthodox Jew, he moved to Brooklyn for religious reasons a couple of years after the last passenger trains left.

“The train is the best way of life here,” he said from Recent York in a phone interview.

“Within the South, individuals are used to living of their automobile. They have a wedding certificate with a automobile,” he said. “It’s the best way it’s. It’s the best way it’s. But listen. I’d like to see the trains come back.”

There are lots of theories to elucidate the decline of U.S. passenger rail. Historians weigh the role of regulation and unions, shoddy business practices, paltry government support or an independence-minded American spirit.

But in keeping with Thomas, one major factor goes generally undisputed — “the rise of the auto and the general public financing of the interstate highway system.”

Buses and cars emerged, but for some time trains retained their benefits. Early-to-mid Twentieth century passenger trains between Atlanta and Chattanooga took about 4 hours, Brainard said. The competition was U.S. Highway 41, which took about as long and, in those early days of the inner combustion engine, entailed certain risks.

“Your fuel pump goes out, you’ve to go knock on some barn or something,” Brainard said. “You are out of luck in middle-of-nowhere Georgia.”

That state of affairs didn’t last. Cars became reliable. The federal government built major airports. Soon passenger salesmen, with all their luggage in tow, took the plane reasonably than the train, Brainard said.

Those trends reversed dramatically, if fleetingly, during World War II, when troops were on the move and rubber and gas were scarce.

“You could not get a seat on a train in Chattanooga,” Steinberg said of those childhood years. “But after the war, it was throughout. Throughout.”

INTERSTATE ERA

Railroads within the nineteenth century expanded on the premise of vast public support, either from the federal or local governments, said White, the train historian. But he said there are major contrasts between that history and the profound nature of federal government involvement within the interstate highway system.

Envisioning that recent system within the mid-Twentieth century, planners heeded the teachings from the nineteenth, White said. They designed the system in a deliberate way — with, generally, one path to get to at least one place, White said. And as they built it, the federal government maintained control of the infrastructure, reasonably than facilitating the ownership of personal corporations.

As contractors began to bulldoze vast rights of way through the hills around Chattanooga, the railroads — whose original tracks were graded through thin rights of way with the facility of mules — languished. Passenger rail was steadily delayed by freight trains on lines that lacked side tracks. And the railroad corporations had little space or money with which to expand.

Meanwhile, automobiles, though still vulnerable to breakdowns, had moved well past the putt-putt days during which they left drivers marooned in rural Georgia on the road to Atlanta.

“You’ll be able to get in your 1965 Impala and zoom down there at 70 miles an hour,” Brainard said.

Steinberg was a toddler when he discovered microfilm at the general public library — and when he began documenting his own world, noticing the changes afoot. Where five trains went to Atlanta day-after-day, there have been 4, he said. Six trains to Cincinnati became five.

Finally on Aug.12, 1970, The Chattanooga Times declared a moment long coming: “Historians can record 11:35 p.m., Thursday, Aug 11, 1970, as the top of an era in Chattanooga.”

The last Southern Railway passenger train had left Chattanooga’s Terminal Station, and the 2 major local papers agreed on the cause: costs were high, and riders were few.

Railway officials and employees got here to Terminal Station to mark the occasion and take a final ride back to the Eastern Seaboard, a route made famous by America’s first gold record, “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” But few others showed up.

“Only a silly fella named David Steinberg,” Steinberg said.

The prior day happened that yr to be Tisha b’av, a fasting holiday within the Jewish tradition, commemorating the destruction of two temples. Now he’d come to Terminal Station to reflect on a spot that had long fascinated him.

Within the front, those partitions are 40-something inches thick, he said, with vitreous brick laid in an expensive flemish bond. Southern Railway staff had at all times welcomed him into his station, he said. They were his friends, and so they invited his extensive photography.

Nearby Union Station, run at that time by Louisville & Nashville Railroad, lacked the identical soaring beauty but still had much historical interest. One intercity passenger train still served Chattanooga from that station, but everyone knew its days were numbered. Federal lawmakers created Amtrak to alleviate the passenger-carrying obligations of the private railroads in exchange for the fitting to pay to make use of their tracks — and in its efforts to show a profit, it might drop under-performing lines.

Rail unions and consumer groups protesting the cutback in service had sought to delay the beginning of the brand new system. But Amtrak won out. On May 1, 1971, the brand new carrier took over a lot of the nation’s long-haul passenger rail service, and, as one newspaper put it, sent one-third of American passenger trains into history.

Riders took nostalgic final rides. Shrimp and champagne parties rocked aboard the Panama Limited run between Chicago and Recent Orleans. Young Michael Meadows, who dreamed of being like his grandfather, headed to Chattanooga’s Union Station to take the last Northbound run of The Georgian — his journey memorialized with a mournful headline: “Mike, 5, Rode Northbound Train But There’ll Be No Return Trip.”

A recent era was at hand. That day, the front page of the Chattanooga News-Free Press featured a map of interstates snaking concerning the Eastern United States and declared the emerging system about three-fourths complete.

Work remained in spots, equivalent to the Interstate 24 stretch up Monteagle Mountain. However the newspaper anticipated the success of what for a lot of had long been only a dream: “The time would come when Americans could travel across the complete country and never face a red light or a stop sign.”

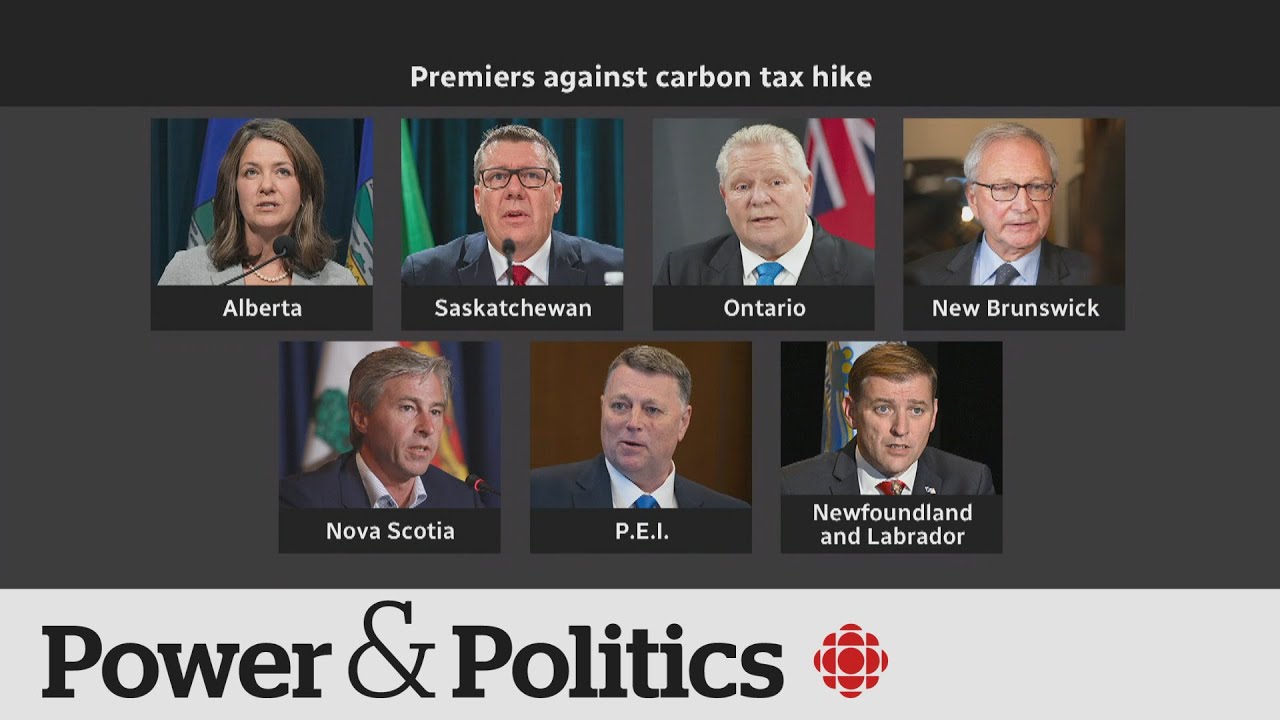

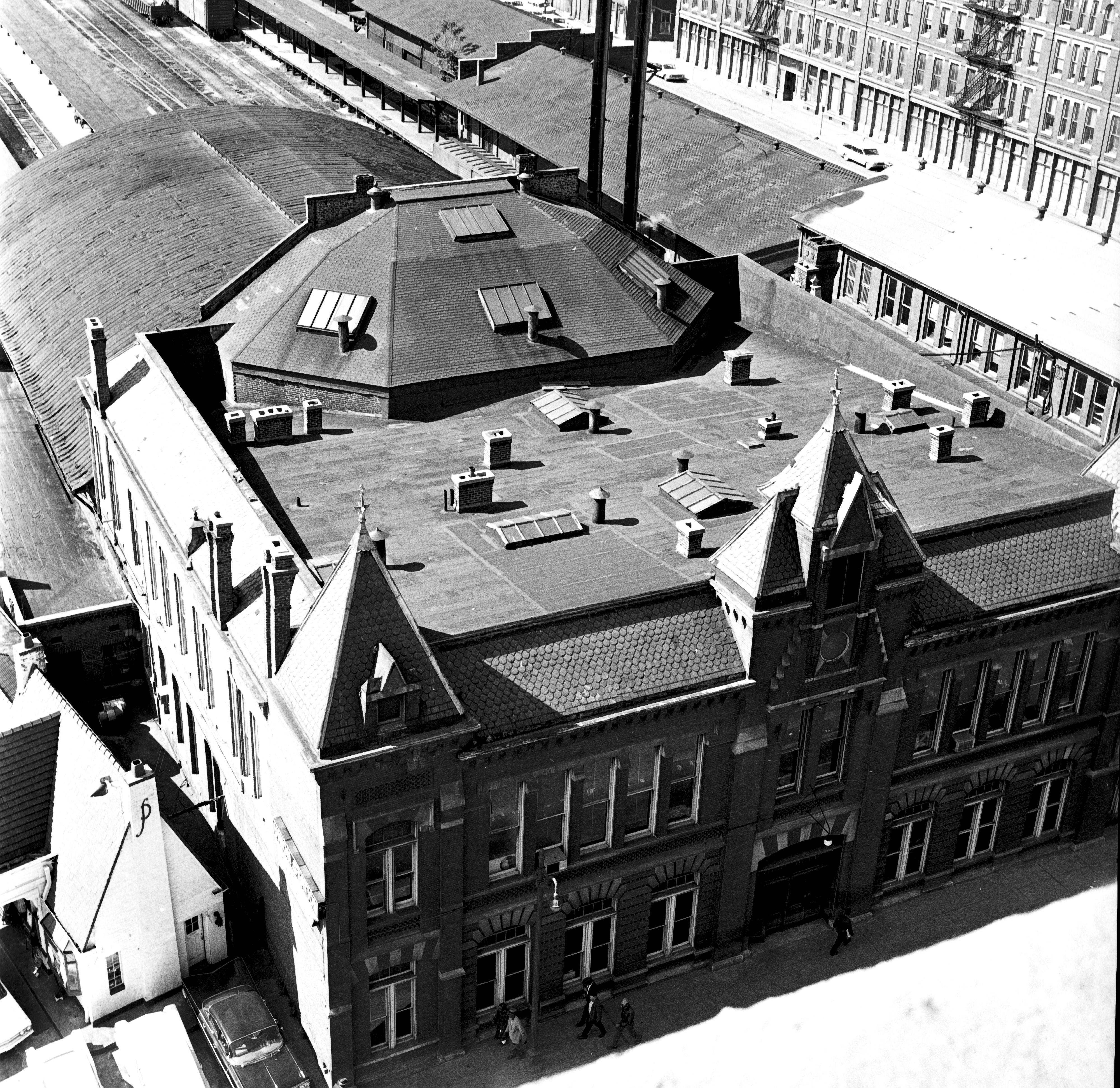

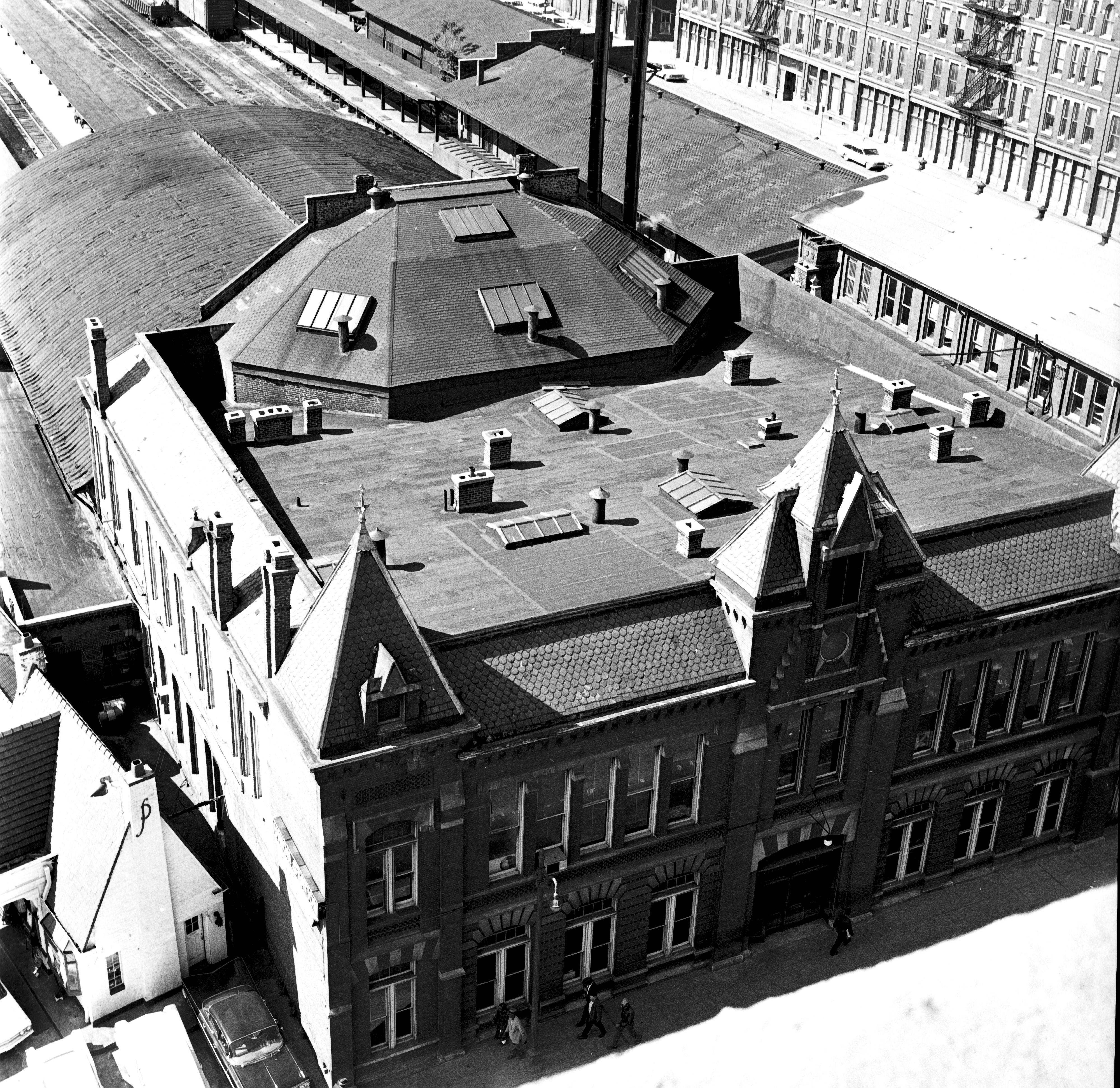

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Union Station, once positioned at Ninth and Broad streets, seen from above in 1963. It was demolished ten years later.

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Union Station, once positioned at Ninth and Broad streets, seen from above in 1963. It was demolished ten years later.NOSTALGIA AND DECAY

The Chattanooga stations’ best days had passed well before the last business passenger trains ran. But by November of 1971, Union Station was grim. Spider webs covered old baggage wagon wheels. Few ventured inside, save lovers, drunkards and the lone railroad official who continued to work there.

“Almost instinctively, he tries to maintain the station looking neat,” the News-Free Press reported, describing the person kicking glass off the old concrete loading platform. “But it surely’s an enormous station, and he’s the one person there. The place could be very still, just a couple of lights on.”

Historical societies and others sought to avoid wasting the station — once amongst the key railway hubs of the South and parts of which predated the Civil War. Those efforts, like many across the country in that era, were a failure: Louisville & Nashville sold a part of its stake to developers, and the station was demolished in early 1973.

Terminal Station, in fact, had more luck — a fact Steinberg attributed to the fierce blowback the Southern Railway received upon razing its historical station in Birmingham.

“That saved Chattanooga,” Steinberg said.

The corporate waited until preservationist-minded buyers got here along.

When those buyers got here, Steinberg heard they planned to keep up a small, nostalgic streetcar line, and he dreamed of operating it.

“But then I assumed to myself ‘David, come on, be realistic. No person’s gonna hire a Jewish fellow that is not gonna work on Friday nights, not gonna work on Saturdays, he’s wearing a beard.'”

He gave up the thought. But then he got a call from B. Allen Casey, who led the Terminal Station purchase — and knew of Steinberg’s railroad research. Steinberg showed Casey, who died in 2020, a few of his archival collection.

“He went berserk,” Steinberg said.

Steinberg said he took his probability and asked Casey if he would hire him to drive the trolley.

It went “nowhere,” Steinberg said — just a fast route across the station’s property. But Steinberg loved the job, which he held into the Eighties, when he grew dismayed at the dearth of Orthodox Judaism on the town.

“My religion was more essential to me, and I felt the void there,” he said. “So I packed my bags and went to a spot I despise with a passion, and that is called Recent York.”

Staff Photo by Robin Rudd/ Engine 9415 leads a southbound Norfolk Southern stack train crosses the Tennessee River on the hundred year-old bridge, recently. Based on Bridgehunter.com the primary bridge was built for the Cincinnati Southern Railway and finished in 1886. The one rounded pier is the one a part of the unique bridge. The bridge was rebuilt from 1917 to 1920. Interestingly the bridge, sometimes called “Tennbridge,” remains to be owned by town of Cincinnati and leased by the Norfolk Southern Railway.

Staff Photo by Robin Rudd/ Engine 9415 leads a southbound Norfolk Southern stack train crosses the Tennessee River on the hundred year-old bridge, recently. Based on Bridgehunter.com the primary bridge was built for the Cincinnati Southern Railway and finished in 1886. The one rounded pier is the one a part of the unique bridge. The bridge was rebuilt from 1917 to 1920. Interestingly the bridge, sometimes called “Tennbridge,” remains to be owned by town of Cincinnati and leased by the Norfolk Southern Railway.Robin Rudd

TRAIN TALK

Today, Tennessee is alive with whispers of trains. Studies are commissioned. Federal money’s flowing. Leaders are sending letters of interest.

State Rep. Yusuf Hakeem, D-Chattanooga, is cutting down on the variety of bills he’ll present this legislative session so he can give attention to his work constructing a passenger rail coalition, he said by phone a couple of days ago. He thinks Chattanoogans might be boarding passenger trains by 2026.

Town, as residents can often perceive, stays a train hub. The usual corporations still run on the usual track network — though their names are slightly different.

CSX, which still runs trains to Atlanta and Nashville, evolved partly from the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, amongst others. And a Southern Railway merger produced Norfolk Southern Railway, which has a big yard on the town and sends freight trains north toward Cincinnati, east toward Knoxville, south toward Atlanta, west toward Birmingham.

Cannot passenger trains just run on those lines? Brainard is skeptical. The old problem of narrow windy one-track wide routes would mean frequent delays, he suspects. A passenger line to Knoxville may not be so tricky, but within the mountains, sidetracks are few, and extra rails can be highly expensive so as to add, he said. Plus, the freight corporations would should be on board, and he thinks they might be wary of sharing the Atlanta route particularly.

“They’ll tell them (Amtrak), ‘You’ve to construct your personal track. You’ve to construct it like an interstate. We’re busy,'” he said.

By law, railroads like CSX have to present priority to Amtrak passenger trains, which outside the Northeast corridor rarely owns the tracks it uses. But in practice, the negotiations are sometimes difficult and have been known to delay or dash passenger rail dreams.

But passenger rail advocates sense a changing climate. As, following passage of a significant infrastructure bill in 2021, the federal government makes what it calls the largest investment in passenger rail because the creation of Amtrak, public officials across the country are scheming and hoping together.

At a hearing Friday, together with Tennessee lawmakers and transportation leaders in Nashville, rail officials from Amtrak and two states related their very own recent experiences expanding passenger rail.

Virginia sought to not force the freight company on the legal requirement to facilitate passenger rail, fearing bad passenger service would result, said Mike McLaughlin, chief operating officer with Virginia Passenger Rail Authority. He said the state as an alternative sought to ascertain win-win arrangements — recent track expansions or outright purchases, for instance — benefiting each the state and the corporate.

Hakeem, by phone, said he imagines in some areas a recent track might be crucial, but he thinks recent logistics technology will ease negotiations with CSX and Norfolk Southern.

“One in every of the aspects is timing,” he said, “and we feel that could be overcome.”

IT’S COME UP BEFORE

As Hakeem knows from his many years in local government, Chattanoogans have seen this talk before.

To call only one Eighties example, Amtrak considered a recent route connecting Nashville and Savannah by the use of Chattanooga — very similar to lawmakers are sketching out today. The Nineteen Nineties and 2000s saw a well-known cycle — but now charged with the promise of recent technology.

Cleveland, Tennessee’s then-mayor, Tom Rowland, spoke to the News-Free Press in 1992 of wonderful possibilities for a recent high-speed route on existing tracks between Washington, D.C., and Chattanooga. The brand new trains, he’d been led to imagine, traveled at 125 mph and tilted on the curves, he said.

Next got here maglev trains, which glide at high speed atop a magnetic field. Around the brand new millennium, a coalition of mayors didn’t secure funding for a project using the technology, but they remained hopeful.

“We’ll see high-speed train service between Chattanooga and Atlanta within the near future,” then-Mayor Jon Kinsey of Chattanooga told the Chattanooga Times Free Press in 2001.

Trains often pull bipartisan support, and in time some politicians got here to imagine a deeper re-imagining was so as.

“I believe when you really need a successful high-speed rail network, then you could have to throw the ball deep,” said Zach Wamp, then a congressman representing Chattanooga, around 2008. “Think like Dwight Eisenhower did with the interstate highway system within the Fifties and put more cash on this and search for bolder technology.”

VALUE PROPOSITION

Chattanooga’s latest plan, focused on short-term feasibility, is way more modest.

“We don’t need to miss good for the right,” Chattanooga Mayor Tim Kelly said during a visit to the Chattanooga Times Free Press offices Thursday.

While high-speed can be great in the longer term, using existing lines can be more financially feasible, said Kelly’s chief of staff, Joda Thongnopnua, who said he has reviewed past passenger rail studies for the world. Such was Kelly’s vision when, in December, he joined the mayors of Savannah, Atlanta and Nashville in signing a letter to the Federal Railroad Administration expressing interest in passenger rail linking the cities.

They were eying a recent federal program, which offers funding and support to initiate recent train corridor studies across the U.S. On the meeting in Nashville on Friday, Nicole Bucich, who heads network development for Amtrak, said the Corridor I.D. program was easy to use to, and was now the perfect — and really, only — way for local governments to use for inter-city passenger rail expansion.

The deadline for the primary round of applications is March 20 — a date Tennessee plans to let pass while it awaits a rail study scheduled for delivery later within the yr.

State transportation leaders, currently planning their very own car-centric efforts to limit traffic congestion, say they’re still interested, and Bucich said there might be a future Corridor I.D. application round, likely in 2024. But in a somewhat unusual arrangement, the group of mayors will themselves apply for the particular Nashville-to-Savannah corridor before the March 2023 deadline, Kelly said, which might mean a federally-backed study of that route could still potentially begin in earnest soon.

It’s unclear, many many years later, if travel times along that route could compete with, say Interstate 75 to Atlanta. Absent a large reforging of the rail lines, Brainard doubts it, and Kelly said if initial studies show the train trip to Atlanta would take something like 4 hours, town probably would not trouble pursuing the thought further.

The opposite query, he said, is where and the way often the train would stop. Advocates imagine that, today as ever, trains have the potential to remake a spot, and towns along the routes will little question pine to be included in any passenger rail plan.

“But when it stops too often,” Kelly said, “you then destroy the worth proposition.”

Contact Andrew Schwartz at aschwartz@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6431.

One Friday within the spring of 1971, 5-year-old train enthusiast Michael Meadows and his grandmother boarded the northbound train to Nashville at Chattanooga’s Union Station. Meadows’ grandfather was a train man, The Chattanooga Times reported, and Michael Meadows hoped to follow suit.

Probabilities looked dim. Young Michael was set to board the last ticketed passenger train to Nashville. The very next passenger train to depart Union Station, southbound to Atlanta, would mark the top of business passenger rail service in Chattanooga.

Michael’s mother, Mrs. William T. Meadows, said she had explained the situation to the boy. “But he just cannot understand why he won’t find a way to ride the train back to Chattanooga when he’s ready to come back home,” she told the Times.

In a city once defined by trains, a version of Michael’s bewilderment would echo for the subsequent half-century. Even intercity bus lines are actually scarce. When you’re a Chattanoogan who desires to get to Nashville, Birmingham, Alabama, Atlanta or someplace else, it’s generally expensive or inconvenient to achieve this and not using a automobile.

Now, prompted by recent potential federal infrastructure money and a way that conditions are ripe for trains to reclaim their lost glory, lawmakers and advocates in Chattanooga are again talking of passenger rail lines to Nashville, Atlanta and beyond.

But, despite the existence of lively freight lines between those and other destinations — which generally run the identical tracks on which passengers once rode — the challenges are steep. State and native lawmakers have talked this talk before — in every decade, in truth, since essentially the most recent ticketed intercity passenger train left Chattanooga, greater than 50 years ago. Is that this time any different?

TRAIN FEVER

Trains, for a lot of today, evoke the hearty spirit of a bygone era. Mark Brainard, who studies the archives on the Southern Railway Historical Association, remembers a grim passing of the guard within the Eighties on the novelty steam train line where he worked in various capacities across the South, because the old engineers didn’t pass their wisdom and elegance to the subsequent generation.

“You bought these guys, 30 years old, used to running a diesel locomotive, that would not play the whistle,” Brainard said from his office near the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum. “They couldn’t work the whistle to present it a soul, right?”

Trains, for people living before us, nonetheless, embodied the astonishing possibilities of modernity.

“Nineteenth-century Americans experienced this radical reordering of their sense of space and time,” said William Thomas, a University of Nebraska historian of the Southern railroads.

Individuals who have lived through the web age might find a way to relate, he said.

Picture yourself. You are in 1820s Savannah, Georgia, where life takes place on the speed you’ll be able to walk.

However the newspapers carry strange tales: Across the ocean, a miraculous device uses steam to maneuver coal on roads of rail.

Skepticism was only natural. “There have been doctors who said, ‘Man cannot breathe air at such a high speed,'” Brainard said.

But train fever was spreading. People saw it as a transformational technology, Thomas said, “not only as an engine of progress, but as something that might transcend nature and help create a society of interconnected places.”

Staff photo by Erin O. Smith / .A Norfolk Southern freight train, lead by rebuild SD-60e no. 6976 makes it’s way down the mainline because the sun sets near Central Avenue Monday, Nov. 13, 2017, in Chattanooga, Tenn. At the fitting Norfolk Southern MP-15DC locomotive, no. 2399 sorts cars at an area industry near the Choo-Choo. Know as East End, quite a few trains a day traverse the world because the mainlines of each the Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads are only yards east of those yard tracks.

Staff photo by Erin O. Smith / .A Norfolk Southern freight train, lead by rebuild SD-60e no. 6976 makes it’s way down the mainline because the sun sets near Central Avenue Monday, Nov. 13, 2017, in Chattanooga, Tenn. At the fitting Norfolk Southern MP-15DC locomotive, no. 2399 sorts cars at an area industry near the Choo-Choo. Know as East End, quite a few trains a day traverse the world because the mainlines of each the Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads are only yards east of those yard tracks.Erin O. Smith

TRACKS LAID

To Georgia power brokers of the early nineteenth century, the Tennessee River promised access to the economies and raw goods of the West. Planners combed the maps. Between Lookout Mountain and Knoxville, there appeared to be a rare natural break within the Appalachian Range granting access to the river.

From Atlanta, builders headed northwest, dodged hills and small mountains, putting together a crooked railroad, stuffed with sharp turns, often inhospitable to multiple tracks, Brainard said.

While paid staff likely numbered amongst them, the people digging dirt and laying tracks were often not working of their very own free will. Thomas said he has consulted every annual report of a Southern railroad company before the Civil War. Those reports, produced for the advantage of shareholders, tallied profits, losses and assets — during which category corporations often reported the financial value of the people they enslaved.

Corporations in those days generally needed to be chartered by local governments; their rights and purposes were approved by lawmakers. Based on Brainard, Tennessee’s had made a decree: the railroad have to be within the state by 1849, lest the constructing company lose its rights.

By 1847 the tracks reached Dalton, Georgia, quite near Chattanooga — at the very least because the crow flies. But there was a mountain in the best way. Squeezed for time, staff left out it, leaving the tunnel for later, Brainard said.

They laid tracks from the opposite side of Chetoogeta Mountain, and arrived in Chattanooga in late 1849, with the road terminating around what’s now M.L. King Boulevard, Brainard said. Speculators, foreseeing a boom town, had bought all the things for a mile up from the river.

Soon the tunnel was accomplished, and the Western & Atlantic Railroad linked Chattanooga to an emerging railroad network that prolonged to the Atlantic. The brand new train terminus had its flaws. Down river toward Signal Mountain in those pre-dam days turned out to be at times almost un-navigable, given the whirlpools — “the suck,” it was called — a fact Indigenous groups were well aware of, Brainard said.

Still, Chattanooga’s identity was set. Soon, recent train lines stretched from Chattanooga into Knoxville and on toward mid-Atlantic cities. Recent tracks looped southwest with the river after which veered toward Nashville, supplanting the circuitous river routes or mud-slogged wagon trains through which, Brainard said, its wealthy residents previously got their fabrics, forged iron or Champagne from France.

Chattanooga Public Library / Three unidentified men in a locomotive belonging to the Roane Iron Company, which was incorporated in 1867 and positioned on the Tennessee River.

Chattanooga Public Library / Three unidentified men in a locomotive belonging to the Roane Iron Company, which was incorporated in 1867 and positioned on the Tennessee River.A WORLD CONNECTED

Chattanooga’s rail and river connections helped make it a strategic treasure within the Civil War, and after the fierce fighting ended, the railroad system continued to chaotically grow.

“They duplicated routes on a regular basis,” said Richard White, a Stanford historian who has extensively studied the financing of the railroads. “When you want chaos — and never everybody goes to agree with me on this — leave it as much as the private sector,” he said by phone.

Though the federal government famously poured in money and land grants for the transcontinental railroads, the Southern railroad was mostly a state- and privately-funded affair. Even local governments eventually pulled out, nonetheless. The highly competitive railroads often lacked the traffic to sustain themselves, and by the 1870s, railroads were going bankrupt, often leaving the general public holding the bag and engendering skepticism toward further government involvement, Thomas said.

The Jan. 19, 1880, Recent York Times captured the frantic energy of the train business, with an article describing “an enormous railroad scheme.” The Louisville and Nashville Railroad Co. had bought the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, putting to rest an epic rivalry during which, in keeping with the paper, the latter company had “set secretly and vigorously to work to checkmate” their competitor through a bewildering array of secret purchases, corporate coups, stock manipulations and backroom deals aided by the “influence of Southern friends” — until, eventually, in a Fifth Avenue hotel in Recent York City, the first stockholders of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad accepted there was nothing to do apart from sign away their shares and cede “Southern Railroad Supremacy.”

Chattanooga was the type of place over which such a supremacy was sought. By the Eighteen Eighties, Brainard said, snowbirds from Buffalo to Chicago funneled through Chattanooga, certain for the Florida winter. Trains conferred a unity upon the region. Chattanoogans in that point could take a train to many nearby railroad towns and onward toward every major city, to the south, to the west, to the coasts. The Chattanooga Times had a railroad editor, Brainard said, and its founder, Adolph Ochs, used privately chartered trains strategically to defeat his primary competitor, the Knoxville Sentinel, in a tug-of-war to supply news to railway towns in between.

But by the late nineteenth century, railroad executives had concluded that raft of passenger service was a consistent drain on an organization’s balance sheet, Thomas said. Freight moved en masse, with minimal labor and hassle relative to passenger service. Freight would not die in a crash. Freight couldn’t sue for negligence.

Still, the businesses kept passenger service due to their charter requirements, and the height of American ridership was yet to come back. By the turn of the Twentieth century, rail remained “the one option to move across vast interior spaces,” Thomas said. The beaux-arts Terminal Station opened in Chattanooga in 1909.

Trains for many years remained the medium for the nation and the events that shaped it. They carried mail and knowledge. They enabled the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to cities and economic opportunities within the North. The federal government took control of the trains during World War I, coordinating rates and schedules in an effort to efficiently move soldiers from far-flung regions — Nebraska, California — to the eastern seaboard for deployment.

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Travelers at a train station in 1959.

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Travelers at a train station in 1959.NEW MODES

David Steinberg’s mother told him his first word was “bus.” Born in 1939 in Alton Park on the corner of thirty eighth and Pirola streets, he watched as train cars from the Incline Railway went up Lookout Mountain — and from his porch as trains went forwards and backwards, day and night — the major line of the Southern Railway path to Birmingham.

Starting within the early Fifties, Steinberg took 1000’s of photos of the trains in Chattanooga during their slow and chronic Twentieth century decline and wrote multiple books on trains and buses because the world modified around him.

An Orthodox Jew, he moved to Brooklyn for religious reasons a couple of years after the last passenger trains left.

“The train is the best way of life here,” he said from Recent York in a phone interview.

“Within the South, individuals are used to living of their automobile. They have a wedding certificate with a automobile,” he said. “It’s the best way it’s. It’s the best way it’s. But listen. I’d like to see the trains come back.”

There are lots of theories to elucidate the decline of U.S. passenger rail. Historians weigh the role of regulation and unions, shoddy business practices, paltry government support or an independence-minded American spirit.

But in keeping with Thomas, one major factor goes generally undisputed — “the rise of the auto and the general public financing of the interstate highway system.”

Buses and cars emerged, but for some time trains retained their benefits. Early-to-mid Twentieth century passenger trains between Atlanta and Chattanooga took about 4 hours, Brainard said. The competition was U.S. Highway 41, which took about as long and, in those early days of the inner combustion engine, entailed certain risks.

“Your fuel pump goes out, you’ve to go knock on some barn or something,” Brainard said. “You are out of luck in middle-of-nowhere Georgia.”

That state of affairs didn’t last. Cars became reliable. The federal government built major airports. Soon passenger salesmen, with all their luggage in tow, took the plane reasonably than the train, Brainard said.

Those trends reversed dramatically, if fleetingly, during World War II, when troops were on the move and rubber and gas were scarce.

“You could not get a seat on a train in Chattanooga,” Steinberg said of those childhood years. “But after the war, it was throughout. Throughout.”

INTERSTATE ERA

Railroads within the nineteenth century expanded on the premise of vast public support, either from the federal or local governments, said White, the train historian. But he said there are major contrasts between that history and the profound nature of federal government involvement within the interstate highway system.

Envisioning that recent system within the mid-Twentieth century, planners heeded the teachings from the nineteenth, White said. They designed the system in a deliberate way — with, generally, one path to get to at least one place, White said. And as they built it, the federal government maintained control of the infrastructure, reasonably than facilitating the ownership of personal corporations.

As contractors began to bulldoze vast rights of way through the hills around Chattanooga, the railroads — whose original tracks were graded through thin rights of way with the facility of mules — languished. Passenger rail was steadily delayed by freight trains on lines that lacked side tracks. And the railroad corporations had little space or money with which to expand.

Meanwhile, automobiles, though still vulnerable to breakdowns, had moved well past the putt-putt days during which they left drivers marooned in rural Georgia on the road to Atlanta.

“You’ll be able to get in your 1965 Impala and zoom down there at 70 miles an hour,” Brainard said.

Steinberg was a toddler when he discovered microfilm at the general public library — and when he began documenting his own world, noticing the changes afoot. Where five trains went to Atlanta day-after-day, there have been 4, he said. Six trains to Cincinnati became five.

Finally on Aug.12, 1970, The Chattanooga Times declared a moment long coming: “Historians can record 11:35 p.m., Thursday, Aug 11, 1970, as the top of an era in Chattanooga.”

The last Southern Railway passenger train had left Chattanooga’s Terminal Station, and the 2 major local papers agreed on the cause: costs were high, and riders were few.

Railway officials and employees got here to Terminal Station to mark the occasion and take a final ride back to the Eastern Seaboard, a route made famous by America’s first gold record, “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” But few others showed up.

“Only a silly fella named David Steinberg,” Steinberg said.

The prior day happened that yr to be Tisha b’av, a fasting holiday within the Jewish tradition, commemorating the destruction of two temples. Now he’d come to Terminal Station to reflect on a spot that had long fascinated him.

Within the front, those partitions are 40-something inches thick, he said, with vitreous brick laid in an expensive flemish bond. Southern Railway staff had at all times welcomed him into his station, he said. They were his friends, and so they invited his extensive photography.

Nearby Union Station, run at that time by Louisville & Nashville Railroad, lacked the identical soaring beauty but still had much historical interest. One intercity passenger train still served Chattanooga from that station, but everyone knew its days were numbered. Federal lawmakers created Amtrak to alleviate the passenger-carrying obligations of the private railroads in exchange for the fitting to pay to make use of their tracks — and in its efforts to show a profit, it might drop under-performing lines.

Rail unions and consumer groups protesting the cutback in service had sought to delay the beginning of the brand new system. But Amtrak won out. On May 1, 1971, the brand new carrier took over a lot of the nation’s long-haul passenger rail service, and, as one newspaper put it, sent one-third of American passenger trains into history.

Riders took nostalgic final rides. Shrimp and champagne parties rocked aboard the Panama Limited run between Chicago and Recent Orleans. Young Michael Meadows, who dreamed of being like his grandfather, headed to Chattanooga’s Union Station to take the last Northbound run of The Georgian — his journey memorialized with a mournful headline: “Mike, 5, Rode Northbound Train But There’ll Be No Return Trip.”

A recent era was at hand. That day, the front page of the Chattanooga News-Free Press featured a map of interstates snaking concerning the Eastern United States and declared the emerging system about three-fourths complete.

Work remained in spots, equivalent to the Interstate 24 stretch up Monteagle Mountain. However the newspaper anticipated the success of what for a lot of had long been only a dream: “The time would come when Americans could travel across the complete country and never face a red light or a stop sign.”

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Union Station, once positioned at Ninth and Broad streets, seen from above in 1963. It was demolished ten years later.

Chattanooga Times Free Press Photograph Collection via Chattanooga Public Library / Union Station, once positioned at Ninth and Broad streets, seen from above in 1963. It was demolished ten years later.NOSTALGIA AND DECAY

The Chattanooga stations’ best days had passed well before the last business passenger trains ran. But by November of 1971, Union Station was grim. Spider webs covered old baggage wagon wheels. Few ventured inside, save lovers, drunkards and the lone railroad official who continued to work there.

“Almost instinctively, he tries to maintain the station looking neat,” the News-Free Press reported, describing the person kicking glass off the old concrete loading platform. “But it surely’s an enormous station, and he’s the one person there. The place could be very still, just a couple of lights on.”

Historical societies and others sought to avoid wasting the station — once amongst the key railway hubs of the South and parts of which predated the Civil War. Those efforts, like many across the country in that era, were a failure: Louisville & Nashville sold a part of its stake to developers, and the station was demolished in early 1973.

Terminal Station, in fact, had more luck — a fact Steinberg attributed to the fierce blowback the Southern Railway received upon razing its historical station in Birmingham.

“That saved Chattanooga,” Steinberg said.

The corporate waited until preservationist-minded buyers got here along.

When those buyers got here, Steinberg heard they planned to keep up a small, nostalgic streetcar line, and he dreamed of operating it.

“But then I assumed to myself ‘David, come on, be realistic. No person’s gonna hire a Jewish fellow that is not gonna work on Friday nights, not gonna work on Saturdays, he’s wearing a beard.'”

He gave up the thought. But then he got a call from B. Allen Casey, who led the Terminal Station purchase — and knew of Steinberg’s railroad research. Steinberg showed Casey, who died in 2020, a few of his archival collection.

“He went berserk,” Steinberg said.

Steinberg said he took his probability and asked Casey if he would hire him to drive the trolley.

It went “nowhere,” Steinberg said — just a fast route across the station’s property. But Steinberg loved the job, which he held into the Eighties, when he grew dismayed at the dearth of Orthodox Judaism on the town.

“My religion was more essential to me, and I felt the void there,” he said. “So I packed my bags and went to a spot I despise with a passion, and that is called Recent York.”

Staff Photo by Robin Rudd/ Engine 9415 leads a southbound Norfolk Southern stack train crosses the Tennessee River on the hundred year-old bridge, recently. Based on Bridgehunter.com the primary bridge was built for the Cincinnati Southern Railway and finished in 1886. The one rounded pier is the one a part of the unique bridge. The bridge was rebuilt from 1917 to 1920. Interestingly the bridge, sometimes called “Tennbridge,” remains to be owned by town of Cincinnati and leased by the Norfolk Southern Railway.

Staff Photo by Robin Rudd/ Engine 9415 leads a southbound Norfolk Southern stack train crosses the Tennessee River on the hundred year-old bridge, recently. Based on Bridgehunter.com the primary bridge was built for the Cincinnati Southern Railway and finished in 1886. The one rounded pier is the one a part of the unique bridge. The bridge was rebuilt from 1917 to 1920. Interestingly the bridge, sometimes called “Tennbridge,” remains to be owned by town of Cincinnati and leased by the Norfolk Southern Railway.Robin Rudd

TRAIN TALK

Today, Tennessee is alive with whispers of trains. Studies are commissioned. Federal money’s flowing. Leaders are sending letters of interest.

State Rep. Yusuf Hakeem, D-Chattanooga, is cutting down on the variety of bills he’ll present this legislative session so he can give attention to his work constructing a passenger rail coalition, he said by phone a couple of days ago. He thinks Chattanoogans might be boarding passenger trains by 2026.

Town, as residents can often perceive, stays a train hub. The usual corporations still run on the usual track network — though their names are slightly different.

CSX, which still runs trains to Atlanta and Nashville, evolved partly from the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, amongst others. And a Southern Railway merger produced Norfolk Southern Railway, which has a big yard on the town and sends freight trains north toward Cincinnati, east toward Knoxville, south toward Atlanta, west toward Birmingham.

Cannot passenger trains just run on those lines? Brainard is skeptical. The old problem of narrow windy one-track wide routes would mean frequent delays, he suspects. A passenger line to Knoxville may not be so tricky, but within the mountains, sidetracks are few, and extra rails can be highly expensive so as to add, he said. Plus, the freight corporations would should be on board, and he thinks they might be wary of sharing the Atlanta route particularly.

“They’ll tell them (Amtrak), ‘You’ve to construct your personal track. You’ve to construct it like an interstate. We’re busy,'” he said.

By law, railroads like CSX have to present priority to Amtrak passenger trains, which outside the Northeast corridor rarely owns the tracks it uses. But in practice, the negotiations are sometimes difficult and have been known to delay or dash passenger rail dreams.

But passenger rail advocates sense a changing climate. As, following passage of a significant infrastructure bill in 2021, the federal government makes what it calls the largest investment in passenger rail because the creation of Amtrak, public officials across the country are scheming and hoping together.

At a hearing Friday, together with Tennessee lawmakers and transportation leaders in Nashville, rail officials from Amtrak and two states related their very own recent experiences expanding passenger rail.

Virginia sought to not force the freight company on the legal requirement to facilitate passenger rail, fearing bad passenger service would result, said Mike McLaughlin, chief operating officer with Virginia Passenger Rail Authority. He said the state as an alternative sought to ascertain win-win arrangements — recent track expansions or outright purchases, for instance — benefiting each the state and the corporate.

Hakeem, by phone, said he imagines in some areas a recent track might be crucial, but he thinks recent logistics technology will ease negotiations with CSX and Norfolk Southern.

“One in every of the aspects is timing,” he said, “and we feel that could be overcome.”

IT’S COME UP BEFORE

As Hakeem knows from his many years in local government, Chattanoogans have seen this talk before.

To call only one Eighties example, Amtrak considered a recent route connecting Nashville and Savannah by the use of Chattanooga — very similar to lawmakers are sketching out today. The Nineteen Nineties and 2000s saw a well-known cycle — but now charged with the promise of recent technology.

Cleveland, Tennessee’s then-mayor, Tom Rowland, spoke to the News-Free Press in 1992 of wonderful possibilities for a recent high-speed route on existing tracks between Washington, D.C., and Chattanooga. The brand new trains, he’d been led to imagine, traveled at 125 mph and tilted on the curves, he said.

Next got here maglev trains, which glide at high speed atop a magnetic field. Around the brand new millennium, a coalition of mayors didn’t secure funding for a project using the technology, but they remained hopeful.

“We’ll see high-speed train service between Chattanooga and Atlanta within the near future,” then-Mayor Jon Kinsey of Chattanooga told the Chattanooga Times Free Press in 2001.

Trains often pull bipartisan support, and in time some politicians got here to imagine a deeper re-imagining was so as.

“I believe when you really need a successful high-speed rail network, then you could have to throw the ball deep,” said Zach Wamp, then a congressman representing Chattanooga, around 2008. “Think like Dwight Eisenhower did with the interstate highway system within the Fifties and put more cash on this and search for bolder technology.”

VALUE PROPOSITION

Chattanooga’s latest plan, focused on short-term feasibility, is way more modest.

“We don’t need to miss good for the right,” Chattanooga Mayor Tim Kelly said during a visit to the Chattanooga Times Free Press offices Thursday.

While high-speed can be great in the longer term, using existing lines can be more financially feasible, said Kelly’s chief of staff, Joda Thongnopnua, who said he has reviewed past passenger rail studies for the world. Such was Kelly’s vision when, in December, he joined the mayors of Savannah, Atlanta and Nashville in signing a letter to the Federal Railroad Administration expressing interest in passenger rail linking the cities.

They were eying a recent federal program, which offers funding and support to initiate recent train corridor studies across the U.S. On the meeting in Nashville on Friday, Nicole Bucich, who heads network development for Amtrak, said the Corridor I.D. program was easy to use to, and was now the perfect — and really, only — way for local governments to use for inter-city passenger rail expansion.

The deadline for the primary round of applications is March 20 — a date Tennessee plans to let pass while it awaits a rail study scheduled for delivery later within the yr.

State transportation leaders, currently planning their very own car-centric efforts to limit traffic congestion, say they’re still interested, and Bucich said there might be a future Corridor I.D. application round, likely in 2024. But in a somewhat unusual arrangement, the group of mayors will themselves apply for the particular Nashville-to-Savannah corridor before the March 2023 deadline, Kelly said, which might mean a federally-backed study of that route could still potentially begin in earnest soon.

It’s unclear, many many years later, if travel times along that route could compete with, say Interstate 75 to Atlanta. Absent a large reforging of the rail lines, Brainard doubts it, and Kelly said if initial studies show the train trip to Atlanta would take something like 4 hours, town probably would not trouble pursuing the thought further.

The opposite query, he said, is where and the way often the train would stop. Advocates imagine that, today as ever, trains have the potential to remake a spot, and towns along the routes will little question pine to be included in any passenger rail plan.

“But when it stops too often,” Kelly said, “you then destroy the worth proposition.”

Contact Andrew Schwartz at aschwartz@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6431.