For those who’ve listened to this week’s episode of “Hark!” on “Good King Wenceslas,” you’ve heard me talk concerning the only mental association I even have with the song. It’s that scene near the climax of “Love Actually” where Prime Minister Hugh Grant goes house to accommodate on Christmas Eve trying to search out the house of his former assistant Natalie. He involves a house where three little girls beg him to sing them a carol, until he finally gives in and he starts singing. And what he and his security officer sing, while the women hop around dancing, is “Good King Wenceslas.”

It’s one in all my favorite scenes within the film, nevertheless it has absolutely nothing to do with the feast of Christ’s birth. From what I can tell, neither does the song. Who is that this King Wenceslas fella? What makes him good? And why does he merit a song at Christmas?

As usual, the facts that producers Maggi Van Dorn and Ricardo da Silva, S.J., uncover concerning the song reveal that the situation is much odder than you may think. It seems Wenceslas was a Tenth-century Christian duke of Bohemia—the modern-day Czech Republic. He was never a king. And while some legends say he was assassinated in consequence of his faith—by his brother on the behest of his mom, no less (and you think that you’ve gotten family drama)—there’s loads of reason to think it was only a straight-up power grab.

And weirdest of all, 900 years later—4 times so long as all the history of america—some English composer thought, “You already know what, there needs to be a Christmas song about that guy.”

Who is that this King Wenceslas fella? What makes him good? And why does he merit a song at Christmas?

I won’t spoil the enjoyment of discovering with Maggi and Ricardo how any of these items make sense. But listening to the song now, I’m struck by the way it functions as a kind of inverted image of one other Nineteenth-century classic, Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol.” Somewhat than hoarding his gold like Scrooge, Wenceslas goes out of his solution to help those that are going without, braving what looks like a reasonably nasty snowstorm to achieve this. And as an alternative of getting to be pushed to alter, the king seems to be an example for others—on this case his poor page.

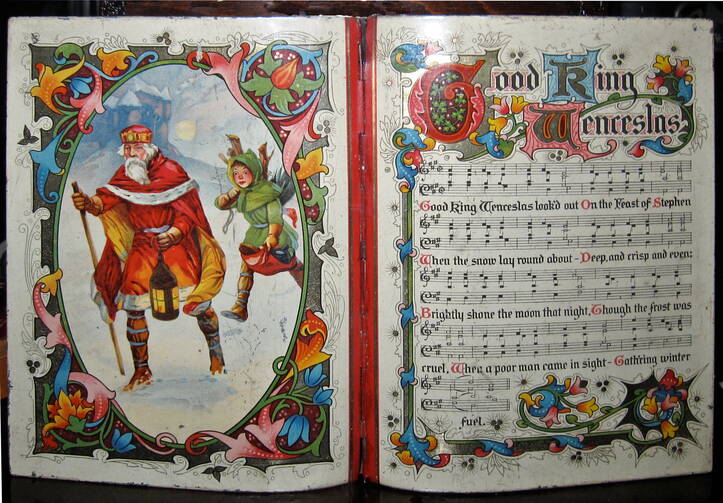

I’m particularly touched by that last section, wherein Wenceslas encourages the page, whose confidence before the nighttime storm is flagging. “Mark my footsteps,” the king tells the page, “tread thou in them boldly. Thou shall find the winter’s rage/ Freeze thy blood less coldly.”

On this season when the wind grows chill and the northern climate grows wet and icy, it is tough not to drag your coat tight and hurry home, irrespective of the needs of the people you meet along the best way. Wenceslas’s words are a strong reminder to me that should you keep your heart open and take a look at to do good, even if you’d slightly just race home, you’ll find refuge not just for others but for yourself.

For rather more great stuff about Good King Wenceslas, take a look at the brand new episode of Hark!, the America Media podcast where we break open the Christmas carols we all know and love.