The novelist Kurt Vonnegut, whose birth centenary we have fun in November, was many things during his 84 years on earth: war veteran, trained mechanical engineer, crime reporter, corporate publicist, used automotive salesman. But perhaps his best contribution to humanity, and the standard that runs because the throughline of his public profession, was the way in which he relentlessly mocked the presumptions of the ruling elite.

Absolutely the refusal to simply accept handed-down truths—whether in politics, science, religion or art—stays the constant in Vonnegut’s life and work. He was not the type of man who believed that anyone should impose his or her concept of the guardrails defining the bounds of acceptable behavior on anyone else.

Perhaps Kurt Vonnegut’s best contribution to humanity was the way in which he relentlessly mocked the presumptions of the ruling elite.

Here is Vonnegut from his debut novel, 1952’s Player Piano:

The sovereignty of america resides within the people, not within the machines, and it’s the people’s to take back in the event that they so wish. The machines…have exceeded the non-public sovereignty willingly surrendered to them by the American people… for the nice government. Machines and organizations and pursuit of efficiency have robbed the American people of liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Or from the identical book: “Out on the sting you see every kind of things you possibly can’t see from the middle…. Big, undreamed-of things. The people on the sting see them first.” And, perhaps most apropos, the creator himself, speaking in 1986 on to a U.S. Senate subcommittee debating whether to bar foreign visitors whose views may be uncongenial to the federal government:

All residents are entitled to listen to and state any idea anyone from anywhere may care to precise. And where did I get the notion that there was such an incredible entitlement? I got it from the junior civics course that was given within the seventh grade at Public School 35 in Indianapolis.

Vonnegut had a wry perspective on just about all the human follies he witnessed during his lifetime (1922-2007), and I sometimes wonder what he might need product of the accordion-style cycle of lockdowns and other restraints imposed on us these past few years. Would he have joined the likes of Neil Young and others of the generation of free love and open expression in becoming the type of shrill, get-with-the-program authoritarian chorus they once warned us about? The reply is: One doubts it, but after all we will never know.

I sometimes wonder what Kurt Vonnegut might need product of the accordion-style cycle of lockdowns and other restraints imposed on us these past few years.

‘Be honorable’

Each in a spirit of tribute to Vonnegut’s centenary and for the sheer pleasure of doing so, I recently reread all 14 of the novels he published in his lifetime. As is well-known, his work was quite eclectic. There are authors whose last book may be very like their first. Having learned their trade, mastered it for once and all, they practice it with little variation to the very end. Vonnegut was a really different kettle of fish, moving from barely dotty time-traveling science fiction to pity-of-it-all war horror and back again, all leavened by exasperated satire of the type of “collective make-believes” that make the world go round, the prime examples being, to Vonnegut’s mind, organized religion and mainstream politics. Even probably the most defensible of them are what he calls “foma,” the harmless untruths that render life bearable.

You possibly can perhaps make a distinction between Vonnegut’s earlier work, culminating in 1969’s Slaughterhouse-Five (coping with the Allied fire-bombing of Dresden of February 1945, which Vonnegut, as an American soldier imprisoned by the Germans, was there to witness), counting on ingeniously wrought metaphors and parables as a narrative scaffold, and the last 30 years or so, where he largely abandoned this fictional effort in favor of informal, often acute, occasionally fortune cookie-like, philosophizing on the human condition.

Is there a typical theme to the Vonnegut oeuvre? If that’s the case, perhaps it’s that he was furious with humanity and disgusted by most authority but preferred to vent his spleen in satirical and very often surrealistic terms, reasonably than to shout it from the rooftops. He didn’t see much of a future for the human race, so his advice was palliative reasonably than prescriptive. “Sing within the shower,” he urged in A Man With out a Country. “Dance to the radio. Tell stories. Write a poem to a friend, even a lousy poem. Do it in addition to you possibly can. You’re going to get an unlimited reward. You’ll have created something.” Life, to Vonnegut, was a tough thing to get through, but one needed to make an effort. Or, more instructively, there was this: “If there’s anything they hate, it’s a smart human. So be one anyway. Save our lives and your personal. Be honorable.”

Vonnegut himself described his core mission in life as propagating a “Christ-loving atheism.”

How did Vonnegut decide to broadcast his essential message to humanity? Again, his work shuns the lure of the pigeonhole, though something like “hallucinogenic science fiction, tethered to rage on the corruption of American values” might come close. Vonnegut himself described his core mission in life as propagating a “Christ-loving atheism.” He went about this in his own distinctive way. Take, as an example, Slaughterhouse-Five, which greater than 50 years after its publication still stays the most effective (or definitely best-known) delineation of his basic style, fizzing with ideas to the purpose of genius or idiocy, which solidified the Vonnegut legend.

It’s the type of thing no self-respecting creative writing instructor would ever condone. The novel violates a lot of the conventions of the shape by telling the reader what’s going to occur to every significant character and situation before she or he involves read the scene. It’s not exactly Agatha Christie, in other words, neither is it the usual peacenik fulmination of fury on the madness of war. It includes loads of heavy weather of sadness, but no real thunderstorm of anger on the futility and the waste.

Vonnegut’s book went through an unusually long gestation period—1 / 4 of a century separated the central event of the Dresden bombing and its literary depiction—and a lot of false starts. Having finally settled on the autobiographical form, Vonnegut had the morbid good luck to see his book launched at a time of maximum public disenchantment with the Vietnam War. It resonated immediately.

The novel as an entire is a literary highwire act that involves, amongst other feats, the usage of flashbacks, fast cuts and surrealistic detours behind a Hemingwayesque facade of short, declarative sentences; it also features a sideshow of time travel and alien abductions, with fourth-wall-breaking cameo appearances by the creator himself. On the opening of the book’s last chapter, Vonnegut surfaces to inform the reader that it’s now 1968 and Robert Kennedy was shot two nights earlier. “Martin Luther King was shot a month ago. He died, too. So it goes.”

Joseph Heller’s humor was of the pie-in-the-face school, Vonnegut’s more arch and detached. If Heller was Jerry Lewis, then Vonnegut was Dean Martin.

Wellsprings

Where does Vonnegut rank today within the American literary pantheon? These matters are necessarily subjective, but perhaps his closest peer could be Joseph Heller, and more specifically the energetically sustained gallows humor of Catch-22. Each authors mined a basic lode of anti-war satire, with a wealthy seam of absurdism, but Heller was the more slapstick in his approach. His humor was of the pie-in-the-face school, Vonnegut’s more arch and detached. If Heller was Jerry Lewis, then Vonnegut was Dean Martin.

Perhaps additionally it is value noting that, in step with nearly all the most effective public humorists, Vonnegut led an essentially humor-free life. And maybe this was, in turn, the wellspring of his art. Definitely his personal circumstances were almost satirically bleak. His once wealthy family was impoverished by the Great Depression, causing strain in his parents’ marriage. His mother committed suicide. His older sister died of cancer a day after her husband was killed in a train wreck. After which after all there was the matter of his war service, and more specifically the Dresden ordeal, which he in some way survived only to be sent into the smoking ruins as prison labor with a view to collect and burn the bodies of the victims.

So perhaps it isn’t surprising that Vonnegut’s often superficially funny prose was shot through with a way of despair at humanity’s folly, and that this same essential gloom was never far faraway from his work. A author brought up on the spectacle of charred corpses is more likely to have a unique perspective on life than one weaned on the products of Walt Disney.

A author brought up on the spectacle of charred corpses is more likely to have a unique perspective on life than one weaned on the products of Walt Disney.

Vonnegut also felt that, for all of the accolades and prizes, the literary establishment never took him as seriously as he thought they need to. Perhaps they interpreted his faux-naïf style, love of science fiction and basic decency as being beneath serious study. Gore Vidal once declared Vonnegut to be “exceptionally imaginative,” while Norman Mailer hailed him as “a wonderful author with a mode that remained undeniably and imperturbably his own.” That other daring young man on the Sixties literary trapeze, Tom Wolfe, allowed that Vonnegut “may very well be extremely funny, but there was a vein of iron at all times underneath it which made him remarkable.”

It’s value remembering, nonetheless, that each one these words were spoken by the use of eulogies, when, with just a few notable exceptions, the notoriously venomous literary fraternity treat a fallen colleague with a respect as exaggerated as, a day or two earlier, it could have been astonishing. (Vidal had previously described the creator of the “unreadable” Slaughterhouse-Five as “the worst author in America.”)

Set on the broader canvas of Western literature, we will glimpse in Vonnegut a few of Mark Twain’s disenchanted idealism, and of H. L. Mencken’s world-weary irony, while there is unquestionably something to Billy Pilgrim’s progress in Slaughterhouse-Five that recalls certainly one of Samuel Beckett’s surrealistic clowns, shambling through a barren, bombed-out landscape, the human punchline of some cosmic joke of unfathomable cruelty. By way of Vonnegut’s heirs and successors, there are the likes of John Kennedy Toole and his grand comic fugue A Confederacy ofDunces, the more picaresque end of Hunter S. Thompson’s work and the early novels of PaulAuster, amongst a bunch of lesser spawn.

Set on the broader canvas of Western literature, we will glimpse in Vonnegut a few of Mark Twain’s disenchanted idealism, and of H. L. Mencken’s world-weary irony.

Deft and wry

So it goes. That was Kurt Vonnegut’s catchphrase, and he happened to make use of it in our first exchange of correspondence, around 1998, when the nice creator was in his mid-70s. I had sent him a fan letter, and he wrote back asking me if I’d do him a small favor. I used to be living in Seattle, and Vonnegut wondered if I could supply him with one or two specific details in regards to the local scenery for a story he was writing. “We scribes should stick together,” he added, after apologizing profusely for the imposition. Speak about flattering.

I used to be not less than lucky enough to once see him up close. It was in 2003, and I had read that Vonnegut was appearing at a book event not in my native Seattle but several hundred miles away in Spokane. Vonnegut speaking almost anywhere struck me as well definitely worth the effort and time of travel, and my ancient Toyota and I finally made it across the Cascade Mountains to the lecture hall.

The creator was then in his early 80s. He was a bit slow on his pins and used a walking cane, but still had a formidable cloud of fuzzy gray hair. Pall Mall cigarette in hand (“More tar than the typical brand,” Vonnegut later announced proudly), he hobbled over to where I used to be standing in the midst of a small reception committee, and looked us up and down. “Got any drugs on you?” he asked us. Everyone shuffled around a bit uneasily. Vonnegut remained deadpan. “I’d accept an aspirin,” he added, which someone produced for him.

After his speech, which was wryly funny and deviated significantly from the Bush administration’s concept of the “war on terror,” Vonnegut circulated across the room, trailing a slipstream of stale smoke and beaming affably to the small groups of fans who approached him. Seeing him slowly make his way from point A to B was a bit like watching the old Queen Mary, with a fleet of tug boats servicing the rumpled, but still in his way majestic, corduroy-jacketed figure in our midst.

I finally got the prospect to introduce myself. Vonnegut checked out me blankly for a moment, but then to my surprise suddenly leaned in and embraced me. “This stuff are my idea of hell,” he muttered in my ear, still managing to smile at his young admirers. Someone interrupted us to ask Vonnegut what advice he would give to an aspiring novelist. “Use a pc,” he said.

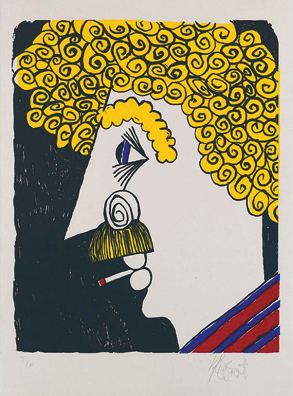

After that, we parted with assurances that we must always keep up a correspondence. My last memory is of seeing Vonnegut silhouetted in a doorway, a tiny figure with hair piled up as high as a guardsman’s fur cap. About six months later, he sent me a replica of his novel The Sirens of Titan, inscribed “Merry Christmas” over a deft little self-portrait and his signature, but that was as close as we got here. Kurt Vonnegut, author and humanist, died in April 2007, on the age of 84. So it goes.